On Tuesday 19th March a group of 54 pupils and 27 members of staff from schools across Northern Ireland had the opportunity to visit the World War I battlefields at Ypres and the Somme. This project was fully funded and organised by the Education Authority.

We were accompanied by Tom Saunders an expert guide from the Somme Association pictured here in front of the Ulster Tower at Thiepval Wood where he is a volunteer. Tom provided us with background information on World War One with extra focus on the part played by Irish/Ulster regiments. His commentary on the places we visited gave the students an excellent insight into the experiences of the soldiers who fought and died in the war.

Our first visit was to Brandhoek New Military Cemetery where we visited the grave of Captain Noel Chavasse, a British medical doctor, Olympic athlete, and Army officer. He is one of only three soldiers to have been awarded a Victoria Cross twice. This is the highest award for bravery in the British army. Captain Chavasse put his own life at risk by going out repeatedly under heavy fire to search for and attend to the wounded who were lying out on the battlefield. Captain Chevasse died in 1917 after being hit by enemy fire whilst attempting to rescue others.

In the evening we visited the Menin Gate in Ypres. A Last Post Ceremony is held here each night at 8pm. The people of Ypres pay a daily tribute to those soldiers who fought and died for their freedom in World War I. The last post is played by members of the Ypres Fire Service and the Mayor recites the poem ‘For the Fallen’ by Laurence Binyon. Poppy wreaths are also laid as part of the daily act of remembrance. This ceremony is attended by people from all over the world.

The Menin gate has 54,600 names inscribed upon its walls. These are the names of soldiers lost in battle whose bodies have never been found.

Soldiers who fought together in war are also laid to rest where they fell in battle, their headstones are erected facing the enemy lines. There are cemeteries and memorials in almost every town and village that we visited in Belgium and Northern France. These memorials were erected to remember the Welsh, Scottish and Canadian soldiers who fought and died during the war.

The Scots were nicknamed ‘the skirted devils’ because of their kilts. Scottish regiments were led into battle by a piper as shown in the statue.

Also known as the Brooding Soldier this memorial was erected to honour Canadian soldiers who died in the very first poison gas attack of World War I. Visible for several miles from its site beside the main road from Ypres to Bruges, the impressive Canadian Memorial at St. Julien stands like a sentinel over those who died. The inscription on the Memorial reads, ‘THIS COLUMN MARKS THE BATTLEFIELD WHERE 18,000 CANADIANS ON THE BRITISH LEFT WITHSTOOD THE FIRST GERMAN GAS ATTACKS THE 22ND-24TH OF APRIL 1915. 2,000 FELL AND HERE LIE BURIED’

The Island of Ireland Peace Park and its surrounding park in Messines, near Ypres in Flanders, Belgium, is a war memorial to the soldiers of the island of Ireland who died, were wounded or are missing from World War I. The tower memorial is close to the site of the June 1917 battle of Messines Ridge, during which the 16th (Irish) Division fought alongside the 36th (Ulster) Division. Conscription was not introduced in Ireland so all of the soldiers from the island of Ireland were volunteers.

There are three pillars giving the killed, wounded and missing of each division

*36th (Ulster) Division – 32,186

*10th (Irish) Division – 9,363

*16th (Irish) Division – 28,398

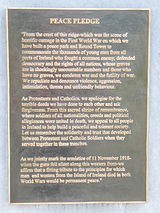

A bronze plaque carrying a peace pledge has been erected in the Peace Park.

A metal sculpture made entirely of poppies also stands in the Peace Park. It includes a white poppy to remember all those killed in war, all those wounded in body or mind. The sculptor wanted to acknowledge all those men who were shot at dawn for cowardice. It is now recognized that many were suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder more commonly known as shell shock, a condition which was not recognized during World War I.

Langemark German Military Cemetery, Ypres Salient, Belgium

This military cemetery began with a small group of German graves in 1915.

Between 1916 and 1918 the burials at Langemark were increased by order of the German military directorate in Ghent. Unlike the Allied cemeteries, the headstones of the German soldiers do not stand upright. The cemetery also holds a mass grave where the bodies of 25,000 German soldiers lie unidentified.

Adolf Hitler visited the cemetery on 1 June 1940 during a two-day tour of the Ypres front where he had served in World War I

Lochnagar Mine Crater Memorial, La Boisselle, Somme Battlefields

This is the largest man-made mine crater created in the First World War on the Western Front. It was laid by the British Army’s 179th Tunnelling Company Royal Engineers underneath a German strongpoint called “Schwaben Höhe”. The mine was exploded two minutes before 07.30 am Zero Hour at the launch of the British offensive against the German lines on the morning of 1st July 1916

The British army used coal miners to undermine/tunnel beneath the German trenches at the Somme. They were paid six times more than a regular soldier. This monument honours their bravery and sacrifice.

The bodies of many soldiers who died in battle have never been identified. So many headstones simply bear the inscription ‘A Soldier of the Great War’. Famous poet Rudyard Kipling suggested that ‘Known unto God’ was written on their headstones. The phrase appears on more than 212,000 CWGC gravestones around the world. Some headstones show regimental emblems where these are known. Many soldiers were identified as belonging to a particular regiment using the brass buttons on their uniforms.

Bodies of fallen soldiers are regularly unearthed by farmers ploughing fields or where construction workers are laying the foundations of roads or buildings. This is the grave of a soldier buried the day before our visit. Where a body has been found, the soldier is buried with full military honours. This soldier remains unidentified but he was a soldier of the Connaught Rangers, an Irish Infantry Regiment, and he has been buried with his fallen comrades.

Millions of tonnes of explosive shells were fired during World War I. Many of these explosive shells failed to detonate upon impact. This one was ploughed up by a French farmer and left at the side of the road for a bomb disposal unit to disarm. It is a 60lb shell and is packed full of explosives. Its brass shell is rusted having been buried for 100 years.

All of the armies in World War I had serving soldiers who were clearly under age. Recruiting sergeants were pain a bonus for every soldier they recruited. This is the grave of Private Valentine J Strudwick who died in combat at the age of 15. He is the youngest known casualty of World War I.

On Christmas Eve 1914 something unexpected happened all along the line of the Western Front. After mercilessly slaughtering each other just hours earlier, men laid down their arms and embraced Christmas together. Soldiers dropped their weapons, climbed out of their trenches and crossed the shell-blasted no-man’s land. Sworn enemies shook hands, sung carols and exchanged gifts. A small number of football matches were played up and down the length of the 500-mile front line, the most famous of which occurred in Belgium, around eight miles south of Ypres. Here, in the fields of the village of Ploegsteert, near Messines, men from both sides played a game of football. This statue stands in their memory.

Thiepval Memorial

On the high ground overlooking the Somme River in France, where some of the heaviest fighting of the First World War took place, stands the Thiepval Memorial. Towering over 45 metres in height, it dominates the landscape for miles around. It is the largest Commonwealth memorial to the missing in the world. The memorial commemorates more than 72,000 men of British and South African forces who died in the Somme sector and have no known grave. The majority of them died during the Battle of the Somme 1916.

Each year on 1 July, a ceremony is held at the memorial to mark the first day of this Battle.

Ulster Tower

The Ulster Tower is Northern Ireland’s national war memorial. It was one of the first Memorials to be erected on the Western Front and commemorates the men of the 36th Division and all those from Ulster who served in the First World War. It is a replica of Helen’s Tower at Clandeboye which was an army training camp during World War I

Thiepval Wood

Thiepval Wood is hallowed ground for many people from Ireland. Although it is now owned by the Somme Association, the wood belongs to the men who still lie beneath its soil. The wood contains excavated World War I trenches which really bring the war and trench conditions to life for the thousands of visitors who come here.

Poperinge

Throughout the War the Belgian town of Poperinge, or “Pops” as the British soldiers called it, was used by the British Army as a gateway to the battlefields Ypres. It was an important rail centre behind the front line and was used for the distribution of supplies, for billeting troops, for casualty clearing stations and for troops at rest from duty in the forward trench areas. Thousands of troops passed through this small town at some time or other.

The Town Hall at Poperinge was also used for Courts Martial or military trials. Men could be imprisoned for drunkenness, failing to return to their quarters or being in the pub during forbidden hours.

For some men these prison cells were death cells where they spent their last hours before being executed. The executions by firing squad were carried out at dawn in the courtyard of the town hall. It is now acknowledged that many of these men who were executed for cowardice were suffering from trauma.